The following is a post I published to Cohost on October 31st of 2022, during the development of Letter to the Golden Witch.

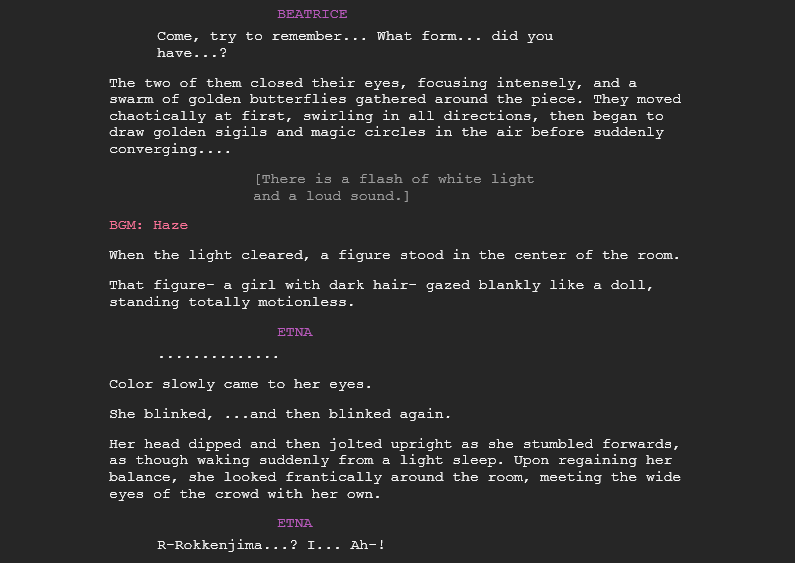

I’ve been in the mines with Letter for some 18 months now; the mines here being the process of turning the text-only raw script (which I had already converted from an MSWord screenplay) into a finished, full-featured visual novel. In that time, the thing that has most struck me about the VN writing process is how difficult it is to predict how well a line will read until you’re looking at it in the VN itself.

Line length and pacing

A passage that reads really well in the script might need to be totally rewritten to look good in a finished context. The relationships between lines are different when you’re writing them in plaintext to when you’re reading them with click markers and page breaks. Lines that seem sensible when you’re looking at the script can look wrong on-screen for all manner of reasons.

Longer sentences are the biggest culprit, since spending too long without a click marker can frustrate readers, encouraging them to just start clicking impatiently through the text scroll rather than taking their time. You can put click markers in the middle of sentences — in fact, this is very common in both Umineko and Letter — but even this must be done with care, to ensure that the natural flow of a sentence isn’t disrupted. Likewise, putting too many click markers close to each other can also be a huge reader pacing issue; multiple short lines are often bundled together to combat this, but a careful balance has to be found.

Another kind of issue that comes up often is when an mid-paragraph click puts a one-or-two letter word like “It” at the end of one line, and the rest of the sentence on the next, potentially disorienting readers and sometimes causing them to miss that first word entirely. This is easily fixed by putting the entire sentence on a new line, but it’s very difficult to predict when the issue will come up until you’ve already seen it happen. This is especially bad when you’re editing and rewriting, since changing a preceding sentence can cause perfectly well-behaved paragraphs to start doing this.

Delays, backgrounds, sprites and vfx

Click markers alone are enough to keep your hands full — but things

like in-line delays, used to add tension to dramatic moments, and the

presence of backgrounds and character sprites complicate matters even

more.

In PONScripter, the engine used by Umineko’s steam release (and

therefore also Letter), any effect or transition will necessarily delay

text appearance by the duration of that effect. There’s no way to have a

transition or effect play out while text is already scrolling – in fact, the only effect that doesn’t fade out the on-screen text is “quake”, which shakes the screen vertically or horizontally for a given amount of time, including any text that is currently visible.

This delay means that Umineko has an inherent, implicit delay to dialogue. When most dialogue is associated with the 300 ms “expression change” effect, it means that dialogue without visible character sprites (a common dramatic technique, the visual novel equivalent of the offscreen dialogue you might see in any film or prestige television show) suddenly carries a different, awkward rhythm, since those transitions aren’t present. Readers can be thrown off if this kind of dialogue appears immediately after a click, rather than 300 ms after — but the problem is solved by adding that delay manually. It’s incredible how much of a difference this can make to a scene’s readability!

The specific ways in which sprites and backgrounds are transitioned to and from can communicate a lot of information, too. If a character falls to the floor, you don’t always want to describe the fall in detail. But if the script only says “Battler fell to the ground” when that’s already implied by a downwards fade of his sprite, a sound effect and shaking screen, then the line is made totally redundant and becomes an interruption of a fast-paced, kinetic scene. You have to cut it, or add some specific detail to it to make it worth keeping.

And transitions are only half of the picture; the mere presence of a sprite or background contextualizes the line displayed in front of it. Does a smirk have to be described if the character sprite is already wearing one of Ryukishi07’s funny expressions? A page of narration over a light fixture has a totally different vibe to one over a set of characters who were just talking to each other. Changing background before a new page of text puts emphasis on the first lines of that page, contributing enormously to the atmosphere that Umineko is famous for. The most striking example is when a line of dialogue is suddenly presented over a black screen, forcing the reader’s attention to the line itself and nothing else. This is something the original work does constantly!

Umineko is a sound novel, not just a visual novel

But where atmosphere and mood is concerned, sound effects and music are the biggest contributors. This is doubly true for a fanwork using a soundtrack like Umineko’s, since readers will have strong and immediate emotional reactions to every single song (or even rain sfx) that starts playing.

As a result of these pre-existing emotional connections, care has to be taken to ensure that a scene is working with its music, rather than against it. It also means, since I’m not adding any new original tracks to Letter, that I have a restricted palette of about 200 songs I can use. Some scenes need music, and some of them will need to be adjusted to more closely suit the mood of the most appropriate track that already exists in the soundtrack. Likewise, scenes with dissonant soundtrack choices will have to be edited to ensure that the contrast between text and sound is just right.

The specific timing at which a song or sound effect starts playing is also important, and I find myself very often making major concessions with my script to make sure that an important song gets all the space it deserves. A fast-paced scene might read fantastically on paper, and it might even be fine to port it into the VN as-is, but slowing down the first few pages to let a song’s introduction play out can elevate the whole experience to a whole new level.

What it meant, and still means, for my process

Getting a scene full of complex transitions and effects to work means paying close attention to the timing and emotional rhythm of the scene, pulling every aspect of presentation from script to music into a single gestalt craft that has to be worked with all together, or not at all.

While putting my first example scenes together, I quickly realized this, and that these factors made heavily editing the raw screenplay (which I had mostly finished drafting by that point) a total waste of time. Beyond making sure things lined up in the big picture — themes, plot threads and the like, which were already mostly-solved problems as a result of working closely to a pre-written outline — worrying about the minutiae of moment-to-moment pacing or awkward phrasing was totally pointless, because every single line in the screenplay would have to be heavily edited or outright rewritten to fit alongside the rest of the visual novel presentation.

So, while going through the process of converting the screenplay into the VN, I chose to skip editing almost entirely, in favor of waiting until I was adding all the assets and effects to each given scene. The screenplay was left as an extremely messy (and unfinished, with several chapters entirely absent) draft, with major changes to it being made in two phases:

First, while literally writing it out again line-by-line into the PONScripter format, where I added basic click markers and made a few more obvious changes. For scenes that didn’t already exist in the screenplay, I put first drafts together directly in the PONSCripter editor itself, with the odd commented-out marker to remind me to add a specific sprite, music track, or set of effects at any points where they’d be necessary.

Second, while putting everything else together, an intense but deeply rewarding process where everything was worked with all at once. Any sets of changes in the text editor had to be immediately checked in the VN window, meaning that I was constantly reading and re-reading every scene, page, or individual line in the VN window itself, while editing on the fly.

That second process is where I still am now, with about 75-80% of the script’s total word count converted into a presentable, ostensibly finished form. Naturally, another proofreading pass will be necessary at some point too, which will encompass all features of the visual novel presentation as well. Maybe it’s no surprise that things are taking so long, eh?

Leave a comment